Can we please play some offense?

on 11.11.22

Recently I listened to a workshop that our local chief of police gave to the Heebieville city council. He was basically giving them a snapshot of all the programs he's got implemented, and what they're addressing, and so on and so forth. In particular, he said that he was hired two years ago to increase dialogue and trust and all these good police reform things, and that the increase in crime was nowhere in the conversation back then, but of course now it's everywhere. His words were that the increase in crime locally is due to more firearms.

Obviously the rise in crime is due to a lot of complex factors, but how are progressives not beating the drum drawing a line between more lenient gun laws and the rise in violent crime? To my ear, it sounds like we've let conservatives completely frame the story on the rise in crime: "Those progressives and BLM types started attacking the police and preventing them from doing their job, and Covid broke down the social structures, and now look what happened." Why aren't we on the offensive on the rise in crime?

Here's a collection of stats on the availability of guns and increase in gun violence, and it clearly long predates the recent spike. But seriously, in a world addicted to fatuous explanations, why can't we make hay out of one that's partially correct?

Non-election Thread

on 11.10.22

Michael Hobbes is obviously a longtime friend of the blog who is now a podcast juggernaut. I listened to the first episode of his new podcast, If Books Could Kill, where they take terrible books with outsized influence in how Americans understand the world (or how journalists portray the world?), and they nitpick the books. The first book was Freakonomics, which is certainly terrible.

Here are two thoughts I have:

1. Michael has a knack for picking amazing co-hosts. And I enjoy Michael himself, and his method of analyzing topics into themes.

2. Obviously Michael left You're Wrong About, and I miss his presence there, where he tackled misunderstood historical events. My problem is with the two others - Maintenance Phase and If Books Could Kill. They both do this thing where they take a deep dive into really shit parts of pop culture, and I find the source material so hideously boring that I don't want to unpack it any further. I just lack curiosity about why something bad is terribly bad. (Sometimes Maintenance Phase tackles bad science, which I find more interesting, or something historical, which I also enjoy. I'm talking about the deep dives into skeevy influencers or terrible diet books which leave me cold.)

I really enjoy all the hosts, but I wish they would talk about something new-to-me and less soul-deadening! Clearly people love Maintenance Phase and they're really doing a true service by unpacking these terrible topics. But it still makes me sad.

Info Snack

on 11.08.22

On this tense election day, how about a light distraction to pick apart?

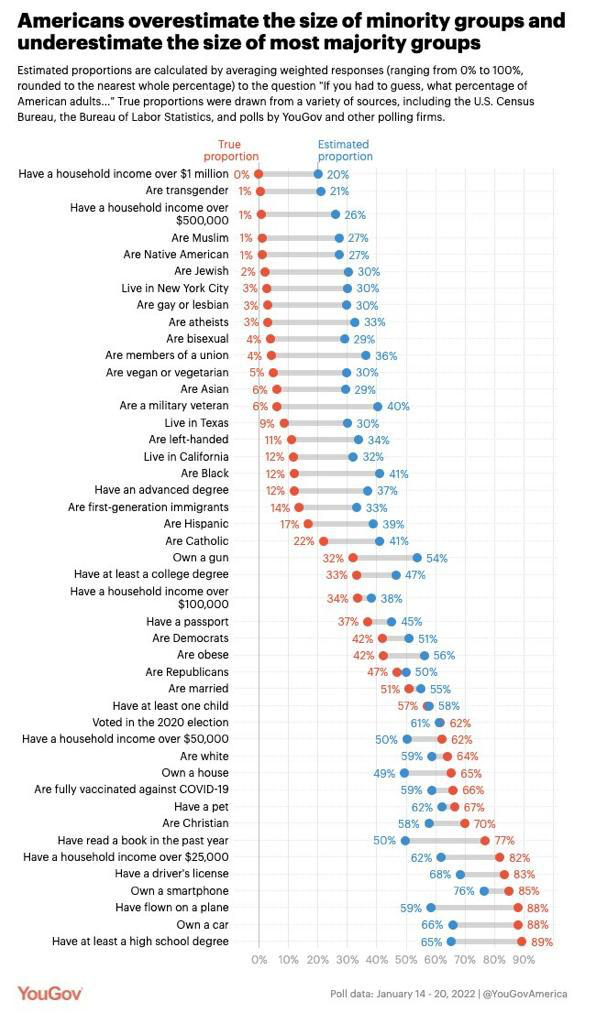

I assume this is an online survey and not all that robust, but we can enjoy it anyway. I'd be interested to know what the misconception-profile is, broken out by Republican/Democrat/Independent, or broken out by where you get your news sourcing from.

Slouching Toward Utopia -- NickS on Chaps 3-5

on 11.06.22

Initial Notes: I've enjoyed writing up my entry, and I hope that someone else will volunteer to take the next three chapters. One of the things that struck me from the first thread was that it is a different book for different readers, and I'm curious to hear what book other people are reading.

I'll outline the three chapters (on Democratizing the Global North, Global Empire, and WWI), and then follow with some broader ideas about the themes (and a criticism of the book), framed with a self-conscious discussion of my own experience as a reader.

Finally, I've quoted significantly from the text, which was doable because, after an earlier post, DeLong was kind enough to share a .pdf. I believe I can offer to send a copy to LB which she could share with people writing other entries.

Democratizing the Global North

Delong frames the book as explicitly about political economy not just an economic history. In this chapter he discusses the general trend towards expansion of the franchise (in the US and Europe) and the challenges to that, as the ways in which it fell short.

He sets the scene by saying that there was a long history of skepticism about democracy.

[I]n the late 1700s next to nobody among the rich and powerful was enthusiastic about democracy."

...

"Madison fervently wanted to avoid the "turbulence and contention" of democracy. Recall that under the Constitution Madison and his peers drew up, states could restrict the franchise as much as they wished, as long as they preserved "a republican form of government.""

...

"Yet from 1776 to 1965, democracy--at least in the form of one male, of the right age and race, one vote--made huge strides in the North Atlantic. The feudal and monarchical systems of government fell into ever greater disrepute."

As the end date of 1965 indicates Delong is conscious of the painful African American history.

Events involving heroic sacrifices of every sort played out over more than a century during the fight for the right of Blacks to vote. Among these were the Colfax Massacre in Louisiana in 1873, during which approximately one hundred Blacks were murdered. At a much less heroic end of the spectrum, when my great-grandmother Florence joined others to launch the Urban League in St. Louis in the 1920s, she became the scandal of her neighborhood by inviting Black people to dinner.

At this point DeLong introduces a longer discussion of Hayek & Polanyi (including the summary I quoted earlier), and connects that to the trend of Democratization by locating an interest in equality in Polanyi, including and expanding Democracy, contrasted with Hayek's concern that giving people more power to override the market will be costly.

There's a discussion of the Progressive movement in US

The Democratic Party of 1900 or so was against plutocrats, bankers, and monopolists. It was for a rough equality. But it was a strange kind of rough equality among the right sort of people. Socialist-pacifists--such as Eugene V. Debs, who besides being involved with the Pullman strikers opposed US entry into World War I--did not belong. And neither did Blacks. Woodrow Wilson was a Progressive, and well respected on the left. He also segregated the US federal government's civil service.

There's then a discussion of African American history framed by the debates between Booker T Washington calling for Blacks to accept an unequal social position in exchange for economic opportunity and protection by the law against racial violence. W.E.B Du Bois is skeptical that this compromise is possible and calls for continuing activism with the goal of full equality.

Then the narrative moves to Europe, where the 18th Century had been more disruptive. Despite -- or because of -- fears of revolution the 19th Century was more stable. In particular, the 40 years before WWI were a Belle Époque -- a period of rapid economic growth and political order (later in the book DeLong will refer back to this period as an economic El Dorado).

In succession after 1791, France experienced the terrorist dic tatorship of the Jacobins; the corrupt and gerrymandered five man Directory; a dictatorship under Napoleon Bonaparte as "first consul"; a monarchy until 1848; a First Republic; a Second Republic; a shadow of an empire under Napoleon Bonaparte's nephew Louis Napoleon; a socialist commune (in Paris at least); a Third Republic, which suppressed the commune and elevated a royalist to president; and, peaking in 1889, the efforts of an aspi rant dictator and ex-minister of war, Georges Ernest Jean-Marie Boulanger, with his promise of Revanche, Révision, Restauration (revenge on Germany, revision of the constitution, and restoration of the monarchy).

And yet land reform stuck. Dreams of past and hopes of future military glory stuck. And for those on the left of politics, the dream of a transformational, piratical political revolution--the urban people marching in arms (or not in arms) to overthrow corruption and establish justice, liberty, and utopia--stuck as well. Regime stability did not, and "normal politics" between 1870 and 1914 always proceeded under revolutionary threat, or were colored by revolutionary dreams.

This was true elsewhere in Europe as well. The continent's nationalities grew to want unity, independence, autonomy, and safety--which first and foremost, especially in the case of the German states, meant safety from invasion by France. Achieving any portion of these outcomes generally entailed, rather than wholesale redistribution, a curbing of privileges, and then an attempt to grab onto and ride the waves of globalization and technological advance. Those waves, however, wrenched society out of its established orders. As class and ethnic cleavages rein forced themselves, the avoidance of civil war and ethnic cleansing became more difficult, especially when your aristocrats spoke a foreign language and your rabble-rousers declared that they were the ones who could satisfy peasant and worker demands for "peace, land, and bread." Increasingly, in those parts of the world without colonial masters, politics became a game without rules--except those the players made up on whim and opportunity. Nearly everywhere and at nearly any moment, the structure of a regime, and the modes of political action, might suddenly shift, perhaps in a very bad way. Representative institutions were shaky, and partial. Promises by rulers of new constitutions that would resolve legitimate grievances were usually empty promises.

In the end, the regimes held until World War I. . . .

Before we get to WWI, however, there's a discussion of Empire

Global Empires

DeLong highlights the challenge of trying to give a summary that is both brief and fair.

Right here I have a narrative problem. The big-picture story of the "global north," or the North Atlantic region, from 1870 to 1914 can be pounded (with some violence) into the framework of one narrative thread. What would become known as the "global south"--that is, countries generally south of, but more importantly, on the economic periphery of, the global north--cannot. And my space and your attention are limited. What is more, a century most defined by its economic history is a century centered on the global north. This, of course, says nothing about cultures or civilizations, or even the relative merits of global north or south in general, or nations in particular. It is merely to assert that the economic activity and advances of the one region of the world causally led the economic activity and advances of the other.

Given this background, what I offer you here are four important vignettes: India, Egypt, China, and Japan. To situate ourselves in these national histories, understand that while 1870 is the watershed year of the global north's economic growth spurt, it is (not coincidentally) the middle of the story of imperialism for the global south. . . .

The four stories are, broadly, about India under the British Raj, efforts in Egypt and China to develop self-sustaining local industries both of which failed, and were taken over be Western powers. By contrast, he says of Japan that it was, "Alone among the non-European world before 1913" in being able to prosper and industrialize.

The details of each story are interesting, but I will offer a long passage discussing the economic logic of empire which had its own coercive power in addition to military might, which I will return to in my broad reactions to the book.

As the twentieth-century socialist economist Joan Robinson liked to say, the only thing worse than being exploited by the capitalists was not being exploited by the capitalists-- being ignored by them, and placed outside the circuits of production and exchange. . . .

It was easier to decide who to bless and who to curse when it came to the formal mode of empire. In the first decades of the long twentieth century, however, making such distinctions became increasingly difficult as the informal mode of the British Empire--and to a lesser extent of other European empires-- gained power. Such are the benefits of hegemony, which had four important aspects: free trade, concentrated industry, free migration, and freedom of investment.

... Most of the nation-states that were extended offers they couldn't refuse ultimately agreed to play by Britain's rules--broadly, for three reasons.

First, playing by those rules was what Britain was doing, and Britain was clearly worth emulating. The hope was that by adopting the policies of an obviously successful economy, you--that is, the government--could make your economy successful, too. Second, trying to play by other rules--say, protecting your handmade textile sector--was very expensive. Britain and company could supply commodities and industrial goods cheaply as well as luxuries that were unattainable elsewhere. And Britain and company would pay handsomely for primary product exports. Finally, even if you sought to play by other rules, your control over what was going on in your country was limited. And there was a great deal of money to be made.

Playing by the rules of the international economic game had consequences.

The first, an aspect of globalization and free trade, was that steam-driven machinery provided a competitive advantage that handicrafts could not match, no matter how low workers' wages. And with very few exceptions, steam-driven machinery worked reliably only in the global north. Manufacturing declined outside the industrial core, and peripheral labor was shifted into agriculture and other primary products. And as a consequence, the global periphery was "underdeveloped." Gaining in the short run from advantageous terms of trade, the peripheral states were unable to build communities of engineering practice that might provide a path to greater, industrial riches.

An essential secondary consequence was that steam-driven machinery worked reliably and steadily enough to be profitable only in the global north. The "reliably" and the "profitable" parts required three things: a community of engineering practice, a literate labor force that could be trained to use industrial technology, and sufficient finances to provide the necessary maintenance, repair, and support services.

Another consequence was the mostly free system of migration in the early years of the long twentieth century (save for Asians seeking to migrate to temperate-zone economies). Finally, free trade and free migration made possible by Europe's informal imperial domination helped to enrich the world greatly in the generations before World War I. Free capital flows, through the freedom of investment, greased the wheels.

WWI

The WWI chapter is a compelling history that covers the pre-war political situation, the initial push for war, and then the struggle for mass mobilization as the countries realized the war was too evenly balanced for a quick vitory by either side. I won't try to summarize in any detail, except to note that:

1) Before the war the economy was strong, and there was good reason for people to know, beforehand, that war would be destructive and illogical.

2) There was strong nationalist popular sentiment.

3) The scale of mobilization was staggering. "In Britain--which attained the highest degree of mobilization--the government was sucking up more than one third of national product ... for the war effort by 1916."

The chapter closes by introducing one of the heroes of the book

[John Maynard Keynes reflected that] He and his [class] had seen "the projects and politics of militarism and imperialism, of racial and cultural rivalries, of monopolies, restrictions, and exclusion, which were to play the serpent to this paradise," as "little more than the amusements of [the] daily newspaper." And "they appeared to exercise almost no influence at all on the ordinary course of economic and social life."

They had been wrong, with awful consequences for the world.

Keynes saw that he was one of the ones who had been so blind and so wrong. And so, for the rest of his life, he took on responsibility. Responsibility for what? For--don't laugh--saving the world. The curious thing is the extent to which he succeeded, especially for someone who was only a pitiful, isolated individual, and who never held any high political office.

General Impression: What book am I reading

In college I majored in Mathematics and Political Philosophy (roughly speaking, what I was good at, and what I got sucked into respectively). I have a moderate generalist knowledge of history and economics. So I am inclined to trust DeLong's factual claims, and am most interested in his descriptions of: how people at the time understood political and economic problems, what happened when that understanding was used to set policy, and how we look back on that with hindsight. As mentioned in the previous thread DeLongs history emphasizes rapid change, and is often a story of massive failures of political leaders and government to solve the problems that they faced. There is a sense throughout of rapidly expanding economic and manufacturing capacity leading to power that was greater than the knowledge and wisdom of leadership (or, conversely, in the case of Fascist and Communist governments overconfidence in their own ability to remake the world with brute force).

The tone of the book will be familiar to readers of his blog. DeLong has asked what that description is meant to convey. If I were to select an illustrative example, I offer his post about Phryne (the "Kim Kardashian" of ancient Greece). In both that post and the book you see an impressive breadth of historical knowledge, fondness for a good anecdote, and an unapologetic presentism in his reading of history. DeLong never buries the humanity in the history that he writes about. He's often empathetic and generous, but the anecdote is directed at how a modern audience sees themselves (and their sense of history) more than recapturing the past. The book is more careful and more subtle than a post which started as a twitter thread, but recognizably the same author.

The book itself, despite the use of Hayek and Polanyi as a framing device, is more of a grand tour of the 20th Century. Hitting the major sites, along with some less well known, but it is intententionally designed to be accessible to a tourist. This inevitably means that, for whatever subject the reader is most interested in or most knowledgeable about, they are likely to feel like the treatment doesn't go into as much depth as it could.

This is ultimately a good choice. I am happy that the book errs in the direction of cataloging what happened, rather than trying too hard to fit a particular theory/grand narrative. As I mentioned in the last post, I wasn't sure, going into the book, what moral weight it would put on the economic history, and the balance of "great and terrible; but more great than terrible" feels generally right. It celebrates the achievement of rapidly expanding economic wealth, without calling the century either a success or a failure. It describes many missed opportunities, but the book generally offers provisional rather than final judgement.

Given my interests, I did want slightly more attention paid to politics and, specifically, I hoped for more in the discussion of power and inequality. There is certainly discussion of those themes; the description of the informal Empire, quoted above, is quite good, but I would have liked to see similar insights in other areas:

-- I thought the discussion of race was occasionally tone-deaf and, compared to the rest of the book, stuck more closely to familiar stories and symbols.

-- There's very little discussion of imigration, and I was particularly conscious of the absence in the later chapter on "Inclusion" and, possibly, as a key global political issue in the early part of the 21st Century.

-- Given the list of three key changes in the organization of human and economic life ("globalization, the industrial research lab, and the modern corporation") there's minimal attention paid to the ways in which those shaped the power of government as well as the economy. Globalization is certainly political as well as technological and possibility of deglobalization is driven by political factors. The industrial research lab and corporation grew in tandem with increased state capacity. It struck me, as I was writing this summary, that the figure cited above -- that the British government was able to mobilize 1/3 the productive capacity of the country for the war effort -- is specific to the long 20th Century (quick googling makes me think the Civil War involved similar levels of mobilization but, I believe, prior to that state capacity was much more limited).

And yet, for any of those criticisms, and places where I wished the book had gone deeper, I am very glad for the tour; it is impressive how much ground it manages to cover, while being good company.

Check Ins, Reassurances, and Concerns, 11/6

on 11.06.22

This is intended to be our system for checking in on imaginary friends, so that we know whether or not to be concerned if you go offline for a while. There is no way it could function as that sentence implies, but it's still nice to have a thread.

Episode Kobe forty-two